Emoji Usage and Zipf’s Law

A linguistic analysis of Emoji usage on Twitter

Zipf’s Law

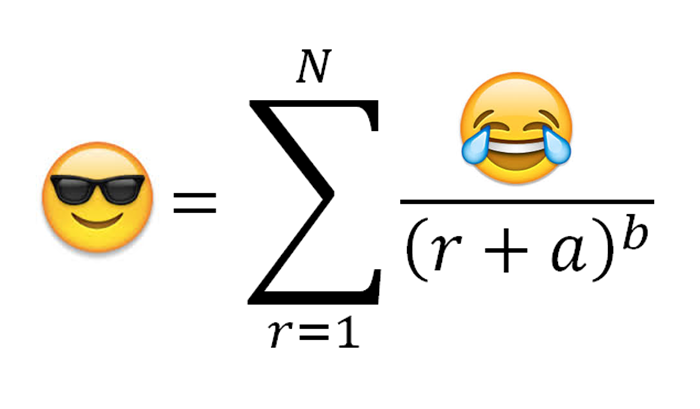

Zipf’s Law is a mathematical rule that states that the frequency of a word’s usage is proportional to power of its rank. The most widely accepted explanation for this phenomenon is the principle of least effort, which basically boils down to: it’s a whole lot easier to remember a smaller set of words than a larger one.

Although the rule was originally derived to explain patterns of word usage in the English language by Harvard-trained linguist George Zipf, Zipf’s Law applied to other natural languages and even extends to areas of Biology, Physics and Sociology. My question was: does it also hold for emoji usage?

Methodology

To test this hypothesis, I knew I needed a large data set, so I went with the largest repository I could find: Twitter. With the help of @mroth who built the amazing emojitracker.com, I was able to access the statistics on the more than six billion emojis that were tweeted between July, 2013 and November, 2014.

Results

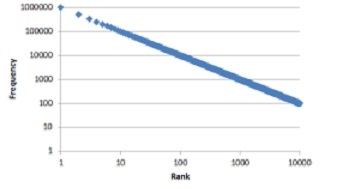

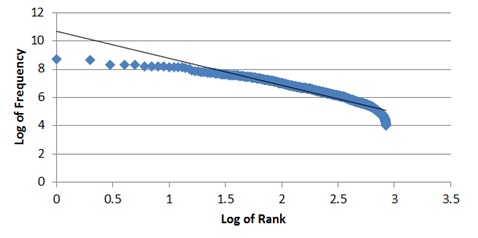

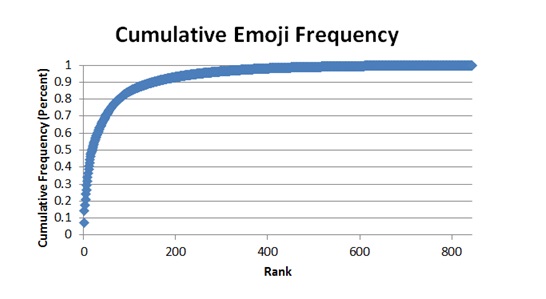

If emoji usage falls under Zipf’s law, then its frequency-rank distribution should conform to a straight line when plotted on a log-log graph:

The reality was something different:

Looking at the distribution, we see that both tails curve downwards. This indicates a relative over-reliance on words of middle rank and an under reliance on words of high and low rank, relative to the Zipf distribution.

Emoji Usage Explained

So what explains the discrepancy?

One likely explanation is dictionary size. As of 2014, the Emoji language was comprised of 845 individual characters. By comparison, the English language has more than one million words.

If one were to roughly apply the least-effort rule to the English language and use only 5% of the English language, they would be left with 20,000 words. If one were to do the same to the emoji library, they would be left with around 40 words, a subset that I think most people would agree is too small to effectively emote with. This might explain why we see a relative over reliance on words of middle rank.

Another way to look at the problem is through the lens of the synonym. For example, how many ways are there to say “confused” in emoji? Not many. By comparison, in the English language, there is an almost endless supply of synonyms for “confused”: “bewildered,” “befuddled,” “disoriented,” etc.

Interestingly, the data is not too far off the Zipf trend line. What this might mean is that if the Emoji dictionary were to expand, then its usage might begin to look more like that of the natural languages.

TL;DR

It’s unlikely that emoji usage conforms to Zipf’s law. Yet another reason why Emoji is not a language.